96. Be a mentor to new birders.

When I was new to birding in November 1975, my mother-in-law and I came upon two birders at the Morton Arboretum outside of Chicago. They approached us and volunteered that they had seen Red Crossbills in a pine stand not far from us and a late Nashville Warbler in another area. I felt honored to be welcomed into the birding brotherhood and offered that we’d seen a pretty good assortment of ducks in a nearby lake, including a lot of wigeons. I didn’t mention that my first American Coots were among them. I had been charmed by the “cute coots with their white snoots,” ruby eyes, and determined way of pumping their necks when swimming. One had even stood on the bank, giving me a great look at its bizarre greenish, lobed toes. These coots were number 110 on my life list, and I had been thrilled to see them, but I had a feeling that these were major-league birders, interested only in rarities. Since the field guide clearly stated that coots were quite common, I didn’t mention them. My mother-in-law, not realizing the careful little dance that birders do to size up one another, blurted out, “There were coots there, too! That was new for both of us!” The two men looked at us disdainfully and walked away.

I was fortunate to know some advanced birders who were extremely welcoming. One of the main forces in the Capital Area Audubon Society in Lansing, a wonderful birder named Joan Brigham, had taken me under her wing and expressed a great interest in all my discoveries. Dave Catlin, an advanced birder and one of my fellow graduate students in the Environmental Education program at Michigan State, shared my excitement when he heard about my first glimpse of warblers. But I’d already learned that the birding community has something of a pecking order. When two birders encounter each other, they engage in a peculiar verbal dance to size up the other, based on not only the size of their lists but also more subtle criteria. Knowing what constitutes a “good bird” is critical, and making any error in identification could mark one as mediocre for life. My fearfulness of making a mistake caused me to be exceptionally wary. One spring I spotted a Summer Tanager—a very rare bird in Michigan—along the Red Cedar River on campus, but I didn’t tell anyone for fear of being questioned and perhaps ridiculed. I’d started birding because birds were so beautiful and fascinating, but somehow my joyful enterprise had morphed into a competitive sport.

Fortunately, by the time I left Michigan for Madison, Wisconsin, in 1976, I’d gotten that silly game out of my system. I’d seen some top birders make errors, and I’d discovered that I would rather bird with people who called out every bird they saw—even if they occasionally had to reassess a sighting and say “Oops”—than with those so intent on being 100 percent accurate that they didn’t call out birds until it was too late for others to see them.

A few birders still play the pecking order game and try to make the birding community exclusive and exclusionary, but most birders realize that the more birders there are, the more likely we are to hear about rarities and the more people there are to work for bird protection. The focus on rarities has become more intense as telephone and Internet rare bird alerts have made it easier to chase down unusual birds. The mission of the American Birding Association has always been to help with the sport of listing—providing birding guides, checklists, and other tools to help birders amass large lists; creating guidelines to make list comparisons meaningful; and publishing a yearly directory of the birders with the largest lists for each state, country, and continent. State ornithological societies also publish such directories, which require one to see a certain number of species. Thus, for some people, the point of the hobby becomes searching out rare birds to bulk up their lists, rather than enjoying all birds.

Even though seeing rarities is exciting and carefully documenting them is important, birding is much more than that. Although it’s easy to fall into thinking “oh, that’s just another grackle,” one of the easiest ways to keep our own enjoyment of common birds fresh is to go birding with beginners. Those grackles that are so abundant (and even annoying after you see one kill a Pine Siskin at your feeder or have to deal with their nestlings’ fecal sacs on your car) have brilliant gold eyes, a shiny purple head, glossy plumage, a long, pointed tail, and a certain macho exuberance. Experiencing this with a beginner can call to mind the excitement of the day long ago when you saw your own first grackle.

Birding with beginners can be fun, but it’s also important for birding itself and for the birds we love. Welcoming newcomers into the fold, patiently listening to their discoveries in the way that Joan Brigham and Dave Catlin listened to mine, giving them useful tips, and showing by example what a joyful enterprise birding is will ensure that birding as a hobby, sport, science, and pastime continues to grow. And in a society that allocates funds based on the size of the interested constituency, the bigger the birding community is, the more likely it is that we’ll be able to keep habitat acquisition and protection on the radar screen of the politicians who make land-use decisions and vote on laws that protect our air, water, and wildlife heritage.

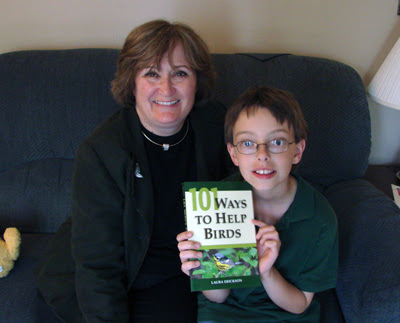

From 101 Ways to Help Birds, published by Stackpole in 2006. Please consider buying the book to show that there is a market for bird conservation books. (Photos, links, and updated information at the end of some entries are not from the book.)