92. Be aware of weather events that affect local birds.

Weather is such an integral part of our day-to-day lives that the weather report is often the most popular part of the evening news, and it’s the one thing people insist on hearing every half hour on the radio. Birds that live outdoors, “naked as jaybirds,” no matter what the weather have an even more intimate acquaintance with it. Some meteorological conditions are literally uplifting for them; others are disastrous. When we become more in tune with the rhythms of nature, we can sometimes avert avian tragedies.

Duluth, where I live, is situated on the western tip of Lake Superior. Every spring, hawks migrate north and end up somewhere along this largest of the Great Lakes. Thousands then make a left turn and follow the Wisconsin shoreline until they clear the tip of the lake right in Duluth. In the fall, as birds head south, they once again hit the shoreline and this time turn right. Either way, to clear the lake, they have to fly over Duluth. Every fall, about 93,000 hawks are counted at Hawk Ridge Nature Reserve in the city; on a single exceptional day, September 15, 2003, a record of 102, 329 were tallied. Fall hawk migration events are correlated with weather patterns; by far, the biggest flights happen on September days with west or northwest winds and high pressure. When one bird feels a rising column of air, it spreads its wings and circles, allowing the thermal to carry it upward in a spiral ascent. When another hawk spies the first one rising, it takes advantage of the thermal, too. Soon there may be dozens, hundreds, or thousands of hawks swirling skyward. From a distance, a small group may look like delicate smoke tendrils or steam rising from a kettle, which is what one of these collections of spiraling hawks is called. Sometimes it looks like a tornado. Sometimes the top of the kettle is too high to observe with the naked eye, but as the hawks reach the point where the air column stops rising, they pull their wings back, arrowlike, and shoot forward, covering as much ground as they can, losing altitude, until they locate another thermal. Thus the birds pour over my city each September, drawing Duluthians’ eyes to the sky.

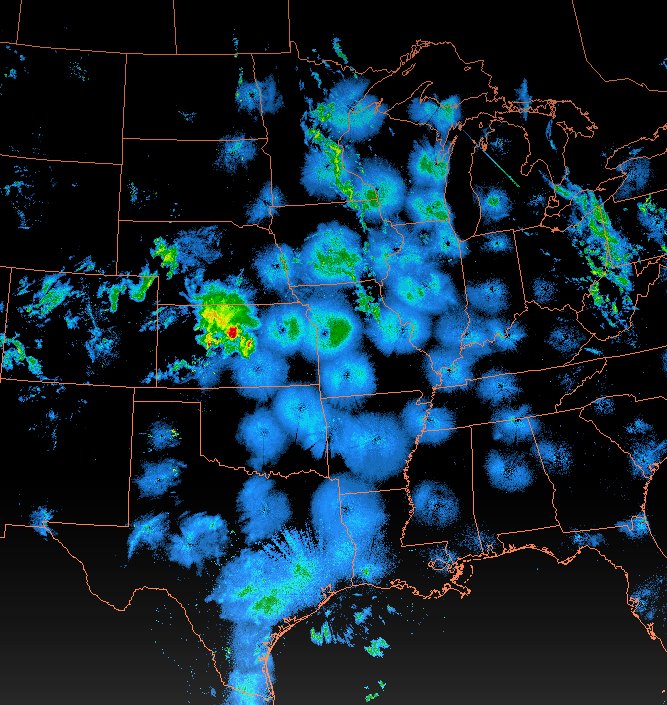

Not all cities have such regularly occurring and spectacular avian events, but weather affects birds everywhere. In spring, robins work their way northward in a band across the continent that pretty much matches the 37-degree isotherm. In the eastern United States, April showers bring the first warblers, and May flowers sustain the first hummingbirds. When we look closely at NEXRAD radar maps on TV or the Internet, sometimes we can see the tattered forms that early radar technicians called “angels,” which indicate large bird or insect movements in the nighttime sky. At first it’s tricky to interpret these maps, but John Idzikowski of the Wisconsin Society for Ornithology put together a simple online tutorial that shows how to read these migrations. On evenings when radar shows a heavy flight, let your radio and television weather forecasters know about it. They may not be receptive at first, but once a weather report starts mentioning wildlife regularly, the positive response from viewers will likely ensure that it becomes an ongoing feature, especially if you and members of your local bird club can give producers a steady and reliable source of interesting information. Bringing birds into local and even national weather conversations keeps them on the public radar screen, even when all we can see on NEXRAD is a storm system. [UPDATE: no longer available but eBird has a great tutorial now]

In large cities, NEXRAD data can tell us which nights represent a clear and present danger to birds. Cities are often built along major waterways where migrating birds concentrate in huge numbers, so even on clear nights, migrating birds may find themselves in the lighted space of a high-rise and collide with windows. In early morning, as migrants descend from the sky to street level, they may find themselves in a concrete maze. When a lost bird spots a lush ornamental tree, it will naturally fly straight for it, even though that tree may be in a hotel lobby with glass blocking the way. In Chicago in the past twenty-five years, about 30,000 birds have been killed by crashing into the glass at McCormick Place alone. It’s a huge problem that occurs in every city, yet most of these deaths are completely and easily preventable if people working or living in the buildings would simply turn the lights off or close the drapes on migration nights. But people need to be reminded when to close the curtains.

That is why the Fatal Light Awareness Program (FLAP) of Toronto came into existence. FLAP works with building owners and managers to encourage them to turn building lights off or pull drapes during migration nights, and it retrieves and aids injured birds come morning. FLAP also works with other cities that want to start similar programs, such as Lights Out Chicago, and it provides information for architects to help them develop less lethal building designs. Volunteers for FLAP and similar programs are pioneers in a world where people integrate nature awareness into daily urban life, which is probably the most fundamental task we face in creating a culture of conservation.

From 101 Ways to Help Birds, published by Stackpole in 2006. Please consider buying the book to show that there is a market for bird conservation books. (Photos, links, and updated information at the end of some entries are not from the book.)