65. Report bird sightings to the local birder hotline, state ornithological society, and eBird.

[UPDATE: AviSys is no longer being updated or maintained. eBird, just getting off the ground when this book was published, has more than lived up to its promises, and will continue long, long into the future, even as it keeps getting better. Also, nowadays more and more birders use digital cameras or smart phones with their spotting scopes to document and report rarities, and social media like Facebook, along with eBird, have become the quickest means of getting the word out about rare sightings.]

Much of what is known about American bird distribution and population levels has been contributed by people who enjoy birds as an avocation rather than a job. Many of the bird specimens that led to the original scientific descriptions of North American birds were collected by army officers and surgeons in the 1700s and 1800s. Abert’s Towhee, Bendire’s Thrasher, Clark’s Nutcracker, Coues’ Flycatcher [now Greater Pewee], Hammond’s Flycatcher, McCown’s Longspur, McKay’s Bunting, Scott’s Oriole, and Williamson’s Sapsucker were all named for American military officers who contributed to ornithology out of a deep personal interest. Arthur Cleveland Bent, who spent many decades compiling the most comprehensive life history accounts of North American birds available until the 1990s, was a businessman. Most of what we know about population increases and decreases in North American songbirds since 1966 comes from volunteer birders through the Breeding Bird Survey, and volunteer birders have provided most of the information available in state bird atlas programs. Only through solid information can any conservation efforts be effective at helping birds.

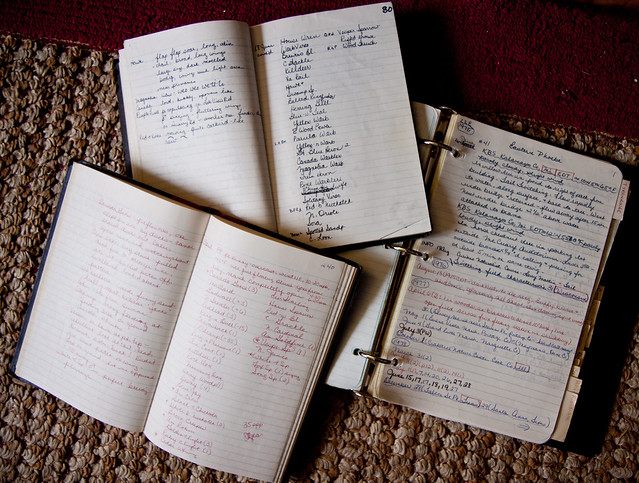

Some birders are “listers,” diligently keeping a life list or separate lists of birds seen in various locations or during specific periods. Other people keep no lists at all. But maintaining field notebooks in which we record the birds seen, the dates and places they were seen, the numbers of individuals seen, and the weather and other conditions provides extremely valuable information for our personal use and for ornithologists and conservationists.

These records can be kept by hand or on computer, Some software allows you to check off species and record the number of birds seen, along with the date and place, in a PDA, which then synchronizes with your computer. [THAT was written before smart phones!] The best software programs allow you to generate reports for specific places or time periods, allowing you to easily report seasonal fightings to state ornithological records committees and to quickly pull up notes about any species.

Keeping records digitally makes them easy to access. I have over a dozen field notebooks from my first years of birding, but it’s very hard to find the specific day in the late 1970s when I found a Bell’s Vireo at my favorite park in Madison or the date that one of my students found a Prothonotary Warbler there. Since the early 1990s I’ve been keeping most of my records on a software program called AviSys. I can now easily look up all the times I’ve seen a Golden-winged Warbler anywhere (as long as I’ve entered the data in AviSys). It takes time to transfer all my old sightings from my field notebooks into this software program, but it allows me to reminisce as I work. The payoff comes when someone needs information about the presence or the absence of a particular species at a particular place during a particular time.

In the event that you spot a rare or hard-to-identify species, recording a careful description in your field notes can be valuable; it can help you decide what you’ve seen and convince an ornithological records committee that you really did see it. Practice drawing birds of various shapes, and pay attention to the various body parts as shown in the front of most field guides. Drawing birds is helpful not only in documenting various species but also in helping you become more observant about shape, color patterns, and other features. Perfecting field skills is something that all good birders, from beginners to advanced, should strive for.

It’s important to share your records. Many localities and most states and provinces have birder hotlines to let interested birders know about rare birds via telephone, email, or cell phone text messages. So when you spot a rarity, share it with others. Sometimes, beginners or even experienced birders make errors. Make sure that you’ve seen all the salient field marks of a rare bird before reporting it. In general, though, it’s better to report a possible rarity, giving others the chance to see and verify your identification, than to stay quiet for fear of being ridiculed.

Most states and provinces have ornithological societies that welcome documented sightings of birds. Find out what organization collects these records in your area. Some take reports over the Internet, and some use written report forms. Unlike local and state birding hotlines, these organizations must verify all unusual sightings to maintain an accurate official checklist of a state’s avifauna, so they have much higher standards of documentation. Don’t be offended if a particular sighting isn’t accepted. It doesn’t affect your own personal lists, unless you’re in a competition. The sport of birding sometimes collides with the science of ornithology, but overall, both benefit from honoring the aims and contributions of the other.

One of the best ways to keep track of your sightings and to benefit other birders, ornithologists, and conservationists in your area and around the world is to report them to eBird. According to its website:

eBird, a project developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society, provides a simple way for you to keep track of the birds you see anywhere in North America [UPDATE–throughout the world]. You can retrieve information on your bird observations, from your backyard to your neighborhood to your favorite bird-watching locations, at any time for your personal use. You can also access the entire historical database to find out what other eBirders are reporting from across North America. In addition, the cumulative eBird database is used by birdwatchers, scientists, and conservationists who want to know more about the distributions and movement patterns of birds across the continent.

The eBird database that you are helping to create can be used by

- you, to track your personal observations and maintain lists of all the birds you’ve ever seen, those recorded at specific locations, or recorded over specific periods of time; or to create lists of birds recorded from various locations and dates based on the records of other eBirders.

- other birders and amateur naturalists, allowing them to learn about the birds in your area

- scientists, to uncover patterns in bird movements and ranges across North America, including migratory pathways, wintering and breeding ranges, arrival and departure dates, range expansions and contractions, and a host of other important environmental relationships.

- conservationists, to identify important areas for birds based on current range distributions, and to track population trends that can be used to create management plans for endangered, threatened, and at-risk species.

- educators, who may use the cumulative database to teach students about birds and the scientific process, including collecting, analyzing, and interpreting results.

- anyone, to discover where species can be found throughout the year; which birds are regularly found at specific locations across North America; when certain species arrive or depart from their breeding and wintering grounds; and many other possibilities.

From 101 Ways to Help Birds, published by Stackpole in 2006. Please consider buying the book to show that there is a market for bird conservation books. (Photos, links, and updated information at the end of some entries are not from the book.)