0. Introduction

Birds are in trouble. How can that possibly be true when gulls and crows, pigeons and geese, blackbirds and sparrows are everywhere? Those birds are adapted to living in urban and suburban habitats or agricultural monocultures. Our burgeoning population and increased demand for gigantic homes and huge manicured lawns encroach upon more and more natural habitat while providing the perfect environment for those animals that share our appetite for grain, ornamental plants, turf grass, and forests cut on short rotation cycles.

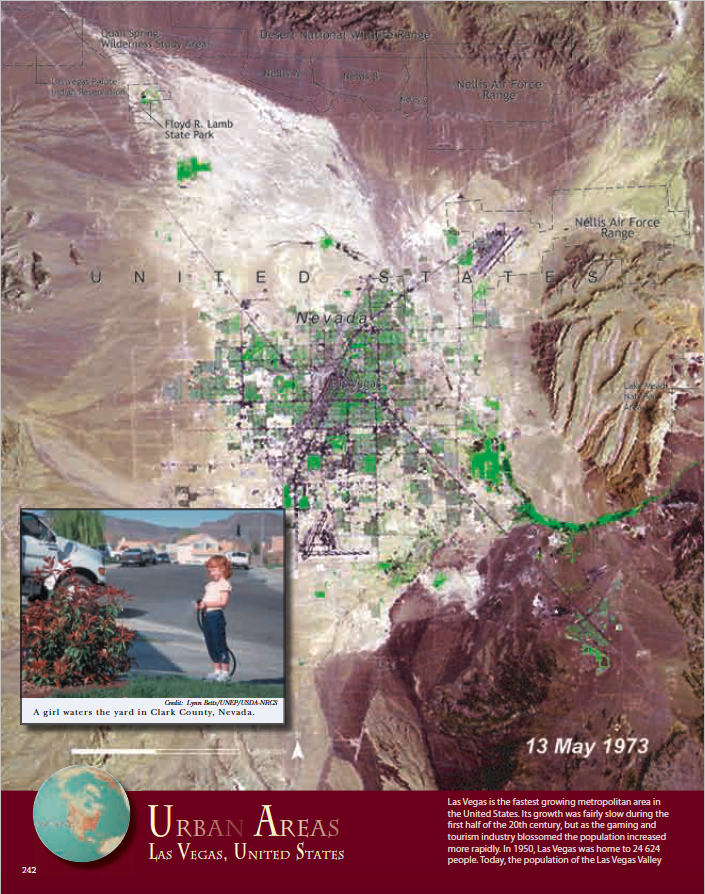

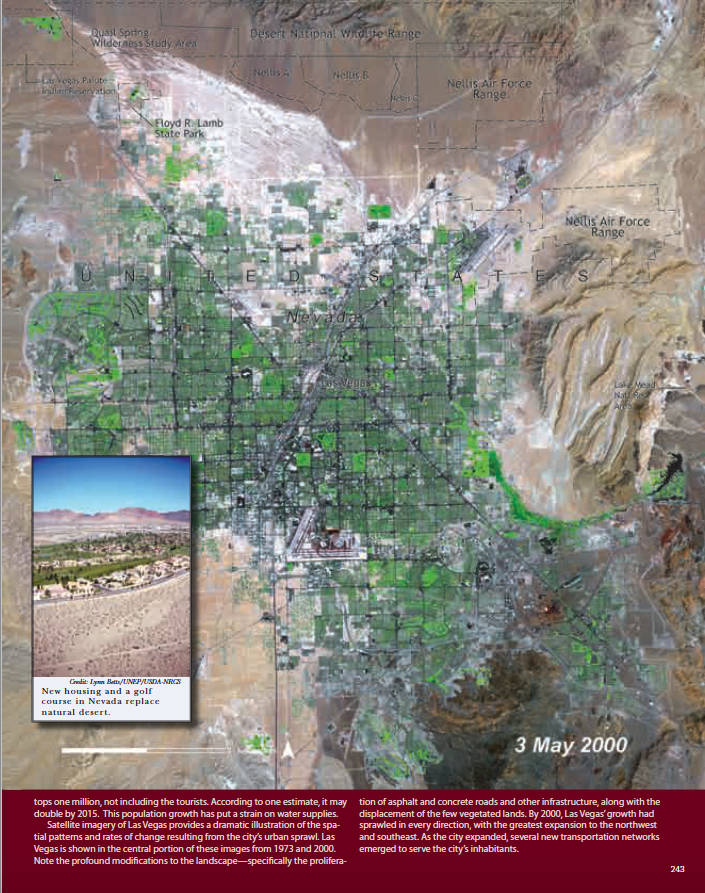

But a great many birds, including familiar and beloved songbirds such as bobolinks, meadowlarks, tanagers, and orioles, require more natural habitats. These are the species that are in trouble. Compare today’s satellite images of just about any place on earth with those taken only a few decades ago to see how much we humans have changed the face of the natural world. How can birds that require relatively wild conditions be expected to maintain steady numbers as so much of their habitat disappears? Dr. Sidney Gauthreaux of Clemson University, analyzing bird migration patterns by radar, found that major migration movements of birds over the Gulf of Mexico declined by 50 percent in just two decades. Studies by the National Audubon Society indicate that fully 25 percent of American bird species are declining significantly. In just the past three years, seabirds have been dying and suffering reproduction crashes at unprecedented levels.

But so what? In a world where human beings are suffering from poverty, hunger, disease, war, terrorism, and natural disasters, isn’t it misguided to spend time and energy trying to help birds? What does that say about our priorities?

Birds Are an Essential Part of Our Lives, History, and Culture

In my own life, wild birds have provided a refuge from childhood terrors and adult pressures, to say nothing of delight and fun. They’ve provided intellectual pleasure, giving me insight into the sciences of taxonomy, ecology, ethology, physiology, and anatomy, as well as geography, history, art, literature, and etymology. Birds have given me, an avid birder, an outlet for my classifying, listing, and organizing side, yet they’ve also given me aesthetic and sentimental joys. In other words, they’ve given me infinite riches for my human heart, soul, mind, and spirit.

But I’m far from the only human being whose life has been enriched by birds. Thomas Jefferson loved birds, mentioning them in detail in his correspondence and his Notes on the State of Virginia. He specifically charged Lewis and Clark with studying and collecting as many birds as possible on their expedition. Henry David Thoreau and Emily Dickinson fed their backyard birds. Franklin Roosevelt found solace in a birding excursion one morning during spring migration. Even the Bible makes mention of birds. In Genesis, Noah sent out a dove to see if the waters had receded after the flood. When the dove brought back an olive branch, Noah was assured that never again would God visit such a flood on the earth. And in Luke 12:6, Jesus said, “Are not five sparrows sold for two pence? And not one of them is forgotten in the sight of God.”

One woman told me about her husband who had suffered a stroke, leaving his arms and legs paralyzed. He became discouraged and clinically depressed; the only thing that lightened his spirits was seeing his backyard birds. My friend would push him in his wheelchair out on their deck, where he’d sit for hours, entertained by birds. He had poor eyesight, so to bring them closer, she began putting mealworms into his paralyzed hands. Wrens, nuthatches, and chickadees quickly started coming to him for treats, and months later, the very first sensation he felt was a chickadee alighting on his finger.

Early on the day after September 11, 2001, when the entire nation was grieving and in shock, and people in the airline industry were particularly hard hit from losing so many of their own, my phone rang and the caller identified himself as the manager of an airline maintenance base. His voice was shaking as he asked, “Are you the Laura Erickson who takes care of birds?” I’d let my bird rehabilitation license expire a few years earlier, but I was too numb and confused to explain, so I just answered “Yes.” He told me that a group of people had rescued an injured pigeon being attacked by crows in the parking lot. He said, “I know a lot of people don’t think much of pigeons, but can you please come and help?”

When I arrived, several men and women stood around the box containing the pigeon, their eyes filled with sadness and hope. Over a bird? The day before, those gleaming twin towers in New York City had collapsed before the entire nation’s eyes, and thousands of human beings were suddenly dead. These people at the maintenance base had watched their TVs like we all did, powerless to do anything. Now one little pigeon needed help, and suddenly there was something they could do to make the world a little less cruel and unfathomable.

As the producer of a radio program, I’ve received hundreds of phone calls and letters from people telling me their own personal stories about birds. I’ve heard from hunters who’ve had lovely or fascinating bird encounters while sitting in their deer stands. And a man in northern Canada called to tell me about his wife’s battle with cancer. The thing that got her out of bed every morning in those final months was the thought of seeing the chickadees at their feeders.

Anne Frank wrote in her diary from her dark hiding place, “The best remedy for those who are afraid, lonely or unhappy is to go outside, somewhere where they can be quiet, alone with the heavens, nature and God. Because only then does one feel that all is as it should be and that God wishes to see people happy, amidst the simple beauty of nature. As long as this exists, and it certainly always will, I know that then there will always be comfort for every sorrow, whatever the circumstances may be. And I firmly believe that nature brings solace in all troubles.”

Helping birds helps human beings.

Birds Are Environmental Indicators

Birds provide humans with incalculable environmental benefits. Songbirds eat a tremendous, unquantifiable amount of insect pests in our forests, prairies, cities, and towns and on our farms. Raptors and shrikes eat huge numbers of rodent pests. And hummingbirds pollinate many plants.

Perhaps equally important, birds are environmental indicators. When I was a little girl, my grandpa had pet canaries, and I remember sitting on his lap, his cheek warm against mine as he told stories about how canaries had saved people’s lives. Miners brought canaries just like my grandpa’s down into the mines with them. The miners often grew attached to the little birds, but the reason they kept them was to detect poisonous gases underground that have no odor or color. Like all birds, canaries have a much faster metabolic rates than humans do, so they react more quickly to a wide range of poisons, from carbon monoxide to pesticides. When a canary suddenly keeled over, the miners knew they had to get out in a hurry. In the same way, when something bad happens to birds in the natural world, we, too, may be in danger.

Of course, other wildlife also reacts to environmental problems. For example, salamanders are far more vulnerable to acid rain than many birds seem to be. So why focus so much attention on birds?

Of all wildlife, birds are the easiest for us to keep track of, so it’s relatively easy to notice when a bird population changes. Birds and humans both rely on sight and hearing over other senses, and we produce visual and auditory signals in similar wavelengths. And more birds are active in the daylight compared with mammals, reptiles, or amphibians, so we notice birds far more easily than we notice salamanders, for instance. Avian territorial singing makes census work for many species a straightforward matter of careful listening and recording, even in the densest forests or deepest grasslands. With regular censuses, we can detect changes in bird populations much more quickly and accurately than we can detect changes in the populations of most other wildlife, and we can quickly discover and react to what is happening, helping not only the birds but also the plants and other animals that associate with them in their habitat. It may seem trivial and unnecessary to protect a single species, such as the Spotted Owl, until one realizes that this species is near the top of the food chain in a specific habitat made up of a great many plants and animals. If something is happening to make the owl decline, clearly something is happening to the northwestern forest ecosystem that may be harder to detect.

There is a huge variety of wild birds—more than 900 species have been recorded in the continental United States, Canada, and our offshore waters. Some, such as common pigeons, crows, and gulls, can survive in a wide range of conditions; these are called generalists. Others that have very specific needs are called specialists. The Yellow-rumped Warbler, a generalist, thrives over a vast range in many habitats, but Kirtland’s Warbler, a specialist, nests only on sandy, well-drained soil beneath young jack pines in north-central Michigan. Kirtland’s Warblers can use a given stand of trees only until the sheltering bottom branches fall off. Then, until fire regenerates the habitat in that area, the warblers must go elsewhere. Barred Owls, generalists, can survive in woodlands young and old, but closely-related Spotted Owls, specialists, require ancient growth. Protecting a single endangered bird can also protect dozens or hundreds of other plants and animals sharing the same ecosystem.

Noticing when birds succumb to various pollutants helps protect us, too. DDT was banned when scientists, such as Dr. George Wallace at Michigan State University, traced huge songbird die-offs to the pesticide, which is stored in fatty tissues. During migration and the breeding season, when fat reserves are quickly metabolized, thousands, perhaps millions, of migratory songbirds were killed outright. Scientists also discovered that Bald Eagles and Peregrine Falcons, which don’t expend significantly more energy during migration than during day-to-day activities, were no longer successfully reproducing because DDT caused eggshell thinning. It took less than two decades of DDT use in the United States to completely wipe out Peregrine Falcons east of the Rocky Mountains and to decimate Bald Eagles and Osprey because of this eggshell thinning.

At the same time that the conservative Nixon administration was banning DDT in 1972, we were discovering that human babies were ingesting this toxin in their mother’s milk, which had worked its way up the food chain after being applied in the outside environment. It wasn’t until 2002 that analyses of blood samples collected and preserved in the 1960s established that DDT in the serum of pregnant women caused low birth weight and premature births. DDT may control the spread of dangerous pathogens when it is applied to the upper walls and ceilings of houses where malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases are prevalent, but when applied to crops, wetlands, residential areas, and other outdoor places, it remains in lethal form in soil, groundwater, and surface water for years, advancing up the food chain until it reaches our own tissues. Ironically, malaria became more, not less, prevalent in most areas where DDT was sprayed outdoors. Mosquitoes, with their short life cycle, can quickly build up a resistance to pesticides, necessitating higher and higher dosages to keep their populations in check. Predatory insects such as dragonflies (which eat mosquitoes) have much longer life spans and lower reproductive rates, making them more vulnerable to pesticides. Thus, pesticides harm an effective and safe mosquito control even as the chemicals themselves become less effective.

When any bird species declines, we know that something it needs is gone or that something bad is happening that may negatively affect humans too.

Protecting Birds and Their Habitats Is a Sound Investment.

We set aside land in the national parks and national wildlife refuges as an investment in the future. As our population mushrooms, these green spaces become more precious, not only for birds but for all of us who live on this planet. In 1872, the year Congress proclaimed Yellowstone the first national park, the entire U.S. population was 38 million, and Yellowstone had 300 visitors. Now, as our national population approaches 300 million, 3 million visitors crowd into Yellowstone each year. In other words, as the human population has grown by an order of magnitude, the number of visitors to national parks has grown by four orders of magnitude. Clearly, parks and wildlife refuges provide increasingly important refuges for humans, too.

But protecting and acquiring new wild areas help more than animals and vacationers. Excess rainwater is far more easily absorbed in wetlands than on concrete. Healthy trees and other plants produce oxygen for all of us to breathe. Clean water and air are essential for our very survival. Healthy forests also provide lumber, paper, and even pharmaceuticals. For example, one of the most effective known treatments for ovarian and breast cancers, Taxol, is derived from the bark of the Pacific yew tree, a slow-growing understory tree found in the virgin rain forests of the Pacific Northwest. The more high-quality habitats we keep healthy, the easier it is for us to continue to thrive, even as our population swells and our country becomes increasingly urbanized.

The Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, and Endangered Species Act were all signed into law during the Nixon administration, which also established the Environmental Protection Agency. It took horrifying a horrifying event such as a stretch of the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland literally bursting into flame in June 1969 for the national will to finally override powerful corporate interests that had a vested financial interest in dumping their wastes into our lakes, rivers, streams, and atmosphere. A river afire is national news. Time magazine described the Cuyahoga in August 1969:

Some river! Chocolate-brown, oily, bubbling with subsurface gases, it oozes rather than flows. “Anyone who falls into the Cuyahoga does not drown,” Cleveland’s citizens joke grimly. “He decays.” The Federal Water Pollution Control Administration dryly notes, “The lower Cuyahoga has no visible life, not even low forms such as leeches and sludge worms that usually thrive on wastes.”

Conditions such as this finally roused the sleeping public, and the Nixon Administration had no choice but to respond. Some three decades later, the majority of Americans have forgotten just how bad things become in short order when industry is unregulated or regulations are not strictly enforced. We citizens must remain vigilant and continue to demand critical environmental safeguards. Our own lives and health, as well as the lives of birds, are at stake.

I sometimes read articles by financial investment advisors who suggest, quite sensibly, that the point of investing is to end up with more money for our future needs and to bequeath to our children and grandchildren. Isn’t that the attitude we need to adopt toward the environment? We need to keep growing our habitat holdings, growing or at the very least maintaining the number of species with healthy populations, and growing the cleanliness of our air, water, and soil for our own future protection and to bequeath to our children and grandchildren.

When my daughter Katie was five years old, I took her to the Bell Museum of Natural History. Her eyes grew big as she looked at the lovely display cases of Passenger Pigeons, so rosy and blue. These “blue meteors” had once filled the skies as the most abundant land bird on the planet. Katie had just started her own bird list and told me she couldn’t wait to see a “real Passenger Pigeon” and add it to her list. I gently explained that the Passenger Pigeon was gone—extinct—and she broke down sobbing in the museum, quaking with sorrow and outrage that people had killed every one.

The story of the Passenger Pigeon is, of course, more complicated than that. Huge flocks lived and wandered and bred together, females apparently ovulating and laying their single eggs in synchrony. Then, as soon as the babies were able to fly, they all left the breeding area en masse. When over-hunting decimated flocks, the remaining birds apparently lacked some critical social stimuli necessary for breeding. Back in the early 1800s, John James Audubon warned that the species couldn’t sustain such heavy hunting for long, but even he continued to shoot them, and the general public simply did not heed the warning. Thus we, supposedly the wisest species on the planet, squandered this magnificent and unique national treasure, one that had provided abundant natural food for us humans as well as for Peregrine Falcons.

Since Katie was born in 1983, we’ve lost the Dusky Seaside Sparrow forever, Bachman’s Warbler has been declared officially extinct, and the Ivory-billed Woodpecker hangs on by a gossamer thread. How many extinct bird species preserved in a museum will Katie show her own children one day? And how will she explain to my grandchildren that it was my generation who squandered their inheritance?

Human Population Is the Biggest Threat to Birds

Wouldn’t it be lovely if there were just a few simple problems that could be easily solved to save birds? Unfortunately, the single biggest threat to birds is a monumental one: human population growth. According to the National Audubon Society’s Population and Habitat Campaign:

During the last 100 years, the world’s population has quadrupled even as per capita consumption of natural resources has skyrocketed. At current birth rates, world population could double in the next 60 years. Even with rapidly declining birth rates, the population of the world is expected to increase by 50 percent in the next 50 years. To put it another way, the world will add more people in the next 50 years than existed in the world in 1950.

While fertility has fallen in many countries and regions, demographic momentum means we are now adding a near-record number of people to the world’s population every year. At present fertility rates, world population could double from 6 billion to 12 billion people by 2060.

As the population of the world has risen from 1.5 billion people in 1900 to over 6.2 billion people today, forests have fallen to farms and freeways at breathtaking speed. As forests have become fragmented, wetlands drained, and coastal areas developed, many migrant song bird species have experience rapid population declines.

Even a cursory glance at the satellite images in the United Nations Environment Program’s massive 2005 book, One Planet Many People: Atlas of our Changing Environment shows the dramatic and often destructive changes that the increasing mass of human beings has made to our planet. Except for limiting the size of our own families and supporting the efforts of national and international organizations to educate people and provide family planning services, there isn’t much we can do as individuals to deal with this staggering issue—the root of most environmental issues and the most critical problem facing birds. But tackling many of the offshoot problems can help birds as well as our own species as we work out ways to improve the standard of living for humans throughout the world for generations to come.

Picture windows kill as many as a billion birds in the United States every year. House cats running loose kill hundreds of millions. Habitat loss eliminates even greater numbers. Lighted tall buildings and communication towers, pesticides, mercury and other toxins, acid rain, automobiles–the list of things that kill massive numbers of birds goes on and on and on. So many things are hurting birds right now that their situation is comparable to that of a person suffering from an autoimmune disease. For example, a patient with AIDS could die from Kaposi’s sarcoma, a cold, or even an infected toe. Once the immune system is compromised, all manner of things can be lethal. Although some conservation issues are much larger than others, they’re all important, and none should be ignored. Every action we take that helps a little is better than doing nothing at all. It is better to light a single candle than to curse the darkness. Of course, the more we do to help birds, the better, but even small steps move us forward. Still, it will take a concerted effort on all fronts to minimize the massive extinctions we face in the twenty-first century.

We All Have a Job to Do.

Many of us love birds for the fun and diversion they provide us, and few of us have expertise in conservation or much stomach for politics. We have so many other responsibilities and pressures in this modern age. Why should we have to assume the burdens of conservation on top of all that?

When I made the decision to have children, it was because I wanted the fun and satisfaction of motherhood—songs and bedtime stories, smiles and giggling, birthday parties and Christmas traditions. Now that my children are in college, I take deep pleasure in their adventures and accomplishments. But suppose I’d wanted children for all the pleasure they provide yet refused to do the work involved in raising them. People may avoid some of the burdens of parenthood by hiring nannies or babysitters. They’re like those of us who contribute money to conservation organizations to do the work for us. If done conscientiously, we can fulfill many of our obligations this way, but we still bear great responsibilities.

Birds are in trouble, and we who love them are obliged to do something about it. To love is an active verb. If God truly notices the fall of a single sparrow, surely he noted the death of an entire race when the Dusky Seaside Sparrow became extinct. In the Bible, God charged Noah with saving every species. According to the Religious Campaign for Forest Conservation:

For reasons rooted in the moral principles of Judaism and Christianity, for reasons of sound science untainted by commercial manipulation, and for reasons dealing with our human responsibility to provide a healthy world for future generations, we see ourselves as morally bound to work for the protection and preservation of the forests and wilderness as crucial elements of the planet’s life support system. We do this as our obedience to God and our service to humanity and particularly the children of today and tomorrow.

Yes, we owe it to our fellow human beings, to future generations whose survival and quality of life will depend on the environment we bequeath to them, and to God himself to protect these irreplaceable treasures.

I wish it were an easy matter to “save birds.” Unfortunately, some of the problems they face are extremely complex, and figuring out the best ways to deal with them will take ingenuity as well as passion and commitment. Is it too late? Is it childish or naïve to hope that we can actually make a difference? Margaret Mead wrote, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

It’s time to roll up our sleeves and get to work.

From 101 Ways to Help Birds, published by Stackpole in 2006. Please consider buying the book to show that there is a market for bird conservation books. (Photos, links, and updated information at the end of some entries are not from the book.)