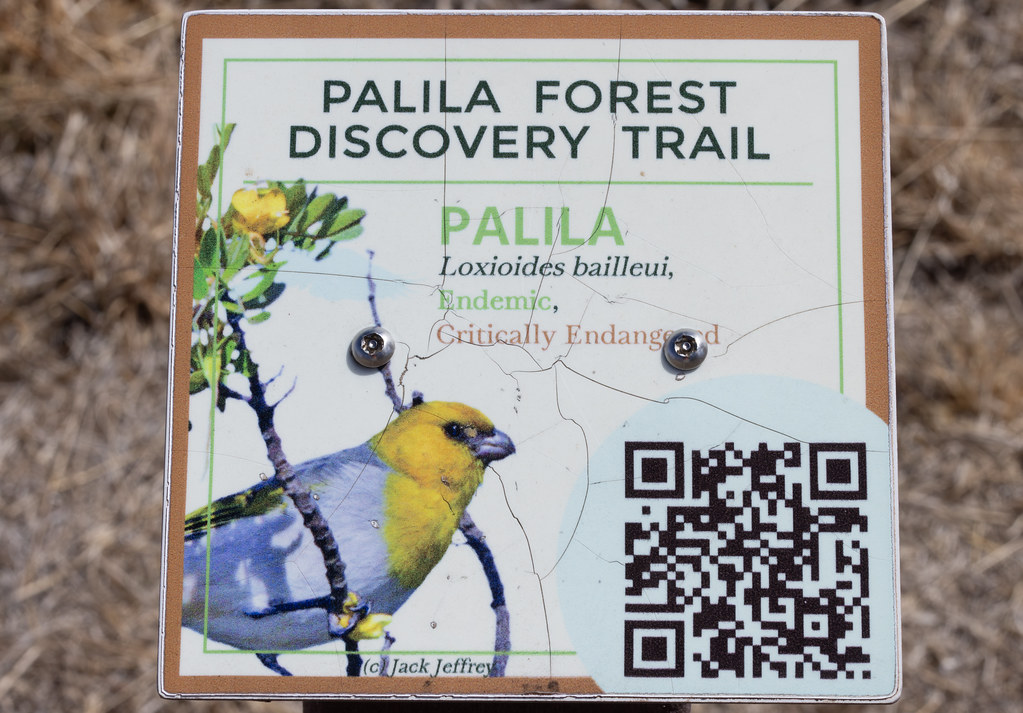

Palila

| Loxioides bailleui | Order: Passeriformes | Family: Fringillidae (Finches, Euphonias, and Allies) |

This critically endangered endemic Hawaiian honeycreeper is famous for being one of the only animals ever to win a lawsuit against a state (1978’s Palila v. Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources). By the time the Endangered Species Act was passed, the Palila’s range had been reduced to just 10 percent of what it had been formerly, on Mauna Kea, Mauna Loa, and Hualālai. By the 1970s, it was limited to Mauna Kea, and even there to just a fraction of where it had once flourished. A mass of records, reports, and studies pointed to feral game animals destroying the bird’s habitat, recommending their total removal from the mountainside. In 1977 the species was included by the US Department of the Interior in a list of 10 extremely endangered animals, bolstering the case.

The defense argued that the feral game animals didn’t feed on or directly injure Palila and thus were no threat to the species, and also that the Tenth Amendment gives states the power to control non-migratory birds within their own borders. But the district court found that the state violated the ESA and ordered it to initiate steps towards the removal of feral sheep (the worst destroyers of the native forest on Mauna Kea) from the island within two years. Plans were approved for the eradication of the feral animals through a public hunting campaign. A request for appeal by the state was denied.

The Palila won the battle but is losing the war. Hunters capitalizing on their reputation as “conservationists” managed to get the state to develop a “conservation plan” to “manage” the invasive feral sheep so hunters could continue their sport wherever they wanted, except in a very tiny fenced-off area, despite continued loss of the māmane-naio forest so vitally essential to Palilas, and the continued dwindling of Palila numbers. These destructive grazers have destroyed what was formerly closed-canopy forest until now, even in the only place Palilas continue to exist, the trees are much more widely spaced than a healthy māmane-naio forest needs.

Palilas are the only Hawaiian honeycreeper with a stout bill, designed to pluck tough, full-sized but unripe, māmane seeds, the primary food source for adults. These seeds are highly toxic to other animals, but Palilas somehow manage to digest them without problem, though scientists suspect that, because the birds do avoid feeding on some māmane trees, they can possibly identify the most toxic ones. When māmane seeds aren’t available, Palilas munch māmane flower buds or even young leaves or buds, but stop breeding entirely until māmane seeds are available again. Other foods are sometimes taken, but constitute a small portion of the diet. These include fruits of another endemic tree, the naio, and caterpillars, which are an especially important protein source for Palila nestlings.

Climate change is another factor in the species’ decline–the Palila’s tiny range is in the midst of a horrible drought, and māmane trees haven’t been producing seeds, meaning Palila have not been breeding, for a few years.

The only time I was ever where I might see a Palila, on March 5, 2024 in a fenced-off preserve with my VENT tour leaders Erik Bruhnke and Kevin Burke and two guides from Hawaii Forest and Trail, I was standing next to Erik when we both heard a distant Palila. They sound enough like Pine Grosbeaks for me to have recognized it instantly even as Erik pointed it out. Kevin saw one a minute or two later, and one trip participant got her binoculars on it as it took off. The four of us were the only ones who actually heard or saw this bird all morning despite an extensive search.

This was the most bittersweet experience of a “lifer” I’ve ever had. Yes, the ABA counts “heard-only” birds–a decision they made decades ago to prevent birders from going to horribly destructive extremes to see secretive species they could easily hear. And as if to verify Erik and my hearing the bird, a few seconds later Kevin Burke and one participant actually saw a distant Palila for a few seconds. But some excellent sources fear that fewer than 300 living Palilas continue to exist anywhere in the known universe, and unless this historic drought ends soon, the species may become extinct within years, not decades. What crappy stewards “conservationists” have turned out to be.